“In this vast whirling chaos there is no end to the sorrow” Du Fu

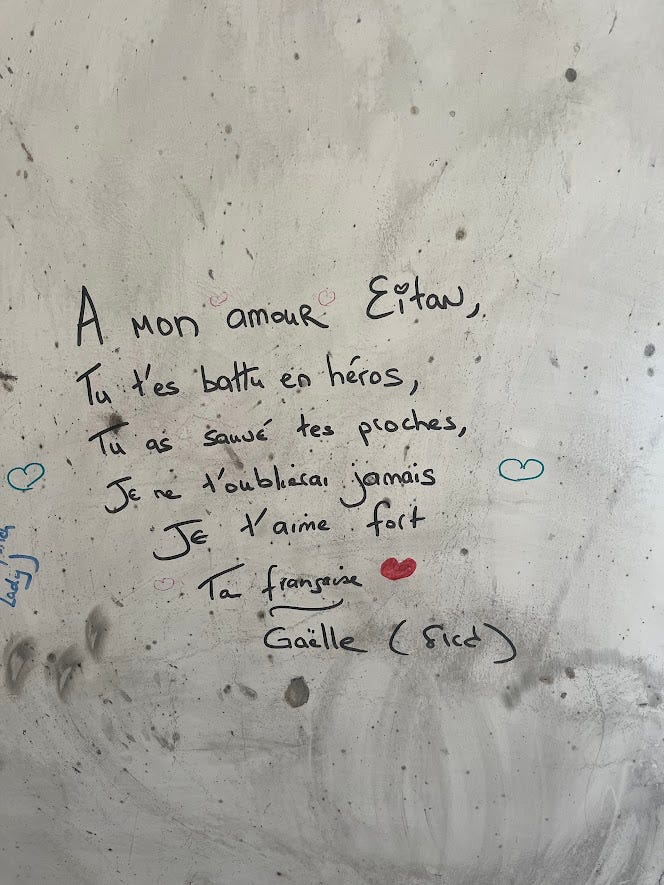

“To my love Eitan,” someone has written at the entrance to the destroyed clinic. “You saved many lives. We will never forget you! I love you. Gaelle (your French lady).” Inside the clinic I see it again, this time in French, with an added first line, “you fought like a hero,” and then, in another room, the English once more. Outside we see Eitan’s picture along with his comrades, each with a cheeky swagger that belies their dreadful fate.

It was just after midday on October 7 and the Hamas terrorists had been in the kibbutz just before 7. There was a medical team inside the dental clinic, treating three injured kibbutzniks, including Gil Boyum from the armed response team. There was the 22-year-old paramedic Amit Man, the 38-year-old nurse Nirit Hunwald, and the 34-year-old doctor Daniel Levi. Outside, Shachar Tzemach and Eitan Hadad had prepared an ambush for the terrorists. Armed with M16s, Tzemach was at the clinic entrance and Hadad was between two cars across the road, shooting the Hamas men as they passed.

The army was only directed towards the unit after 14.00, by which time Shachar and Eitan had run out of ammunition and retreated into the clinic, which by now was being bombarded with grenades. Bereft of any other options, Shachar suggested that Amit try surrendering. “Go out, please,” a survivor, Yair, recalls him saying. “Maybe they will spare you. You are very young.” Before leaving, she texted her family: “Please be strong if something happens to me.” Then, at 14:14, her sister Haviva called. “They are here,” Amit told her. “They shot me in the legs. I’m not going to make it. They’re on me.” Her body was found two days later, with a gunshot wound in her forehead and a tourniquet around her left leg. Shachar, Eitan, Gil, and Daniel were also killed.

***

I visited Be’eri with a group of translators who had volunteered to translate the stories of those murdered on October 7 into English. As a way of saying thank you, the kibbutzniks had invited us to see where the people we had written about had lived and died. It was my first visit to the Gaza Envelope since the war began. I knew many people were visiting the area, and an intense debate had been raging on my tour-guide Whatsapp groups about whether and how to visit the communities that suffered so terribly that day. We weren’t coming as tourists, though. The kibbutz wanted to host us.

The first thing that struck me was how big Be’eri is. Founded as one of the ‘11 points in the Negev’ on 6 October 1946, its population on the eve of the Hamas invasion was over 1,000. 101 civilians and 31 security personnel were killed that day, with 32 taken hostage (11 of whom are still in Gaza). Hamas invaded from three points, but the worst-hit areas were the Olives and Vineyard neighborhood, where mainly older families lived. As we entered the Olives neighborhood, we passed Rami Gold, holding an M16. I recognized him immediately. 70-years-old, a veteran of the Yom Kippur War and creator of mountain-bike trails, on October 7 he had picked up a rifle from an injured kibbutznik who himself had picked up a rifle from an injured kibbutznik, took up a concealed position with a friend, and spent the next 12 hours methodically shooting any passing terrorists.

There is something eternally compelling about a triforce of wisdom, heroism, and stoicism, and Rami exudes these qualities in spades. He and his friend had found a spot on a porch where they couldn’t be seen. “So every person [from Hamas] who passed between the buildings or on the road got shot in the process,” he told an interviewer. “We didn’t eat, we didn’t drink, we didn’t do anything, we just stood there and fought…until we got to the point that we ran out of bullets.” By this time the army had arrived and gave them more ammunition. They remained there until 20:00. Between them they think they injured around 14 terrorists; Rami counted nine dead. “They weren’t scared,” Rami said. “They fell down and kept on going like nothing happened.” When asked how he feels towards the terrorists, he says: “I can go back and do it all over again. And this has nothing to do with rage, it has nothing to do with paying them back, it has to do with the idea that…as a youngster I used to say, to everybody, Arabs as well, if you come in peace, welcome to my home, but if you come in a different way I’m going to wait for you on the fence.”

There were incredible tales of heroism that day, but the main story was one of slaughter. “In this house lived YORAM BAR SINAI who was brutally murdered in the Hamas terror attack on October 7th.” The same sign, with different names, appeared on countless homes, some still standing, but many now burnt-out wrecks. We also saw the letter ‘c’ wrapped in a diamond – a sign that the security forces had written on the houses to indicate that the building was clear of terrorists. We passed the house of the prominent peace activist Vivian Silver, who was believed to have been kidnapped to Gaza until archaeologists identified her remains.

I identify more with this place because it is familiar to me. My wife is from a kibbutz; the look and mannerisms of the residents are similar whichever one you visit; the smells, the layout, the vibes. Like many other Israelis I have imagined what I would have done on October 7, concocted daring acts inspired by Hollywood movies and video games, if only to hide the knowledge that I would have probably been murdered or kidnapped without so much as a squeal of resistance. But our guide, Eyal, had a real Home Alone story. On October 7, he and his family fled into the bomb shelter, along with their dog, Petel, who barked hysterically. They didn’t realize it then, but the baby monitor was on, amplifying the sound of the barks, causing the terrorists to flee. Hearing his story, I regretted not owning either a baby monitor (despite a newborn) or a dog.

We eventually reach the house of Avia Hetzroni, whose story I translated for the website. Amidst a sea of sorrow, what happened to his family stands out in its bleakness. Avia Hetzroni, more commonly known as ‘Avoyha,’ who was born in 1954, had volunteered at the MDA station in Netivot and was part of the clinic team at the kibbutz. Everyone on the kibbutz knew him – he gave lifesaving first-aid treatment, drove people to hospital, and once even acted as a midwife. The joke on the kibbutz was: “If the first face you see in the morning in bed is Avoyha, it’s a sign that you’re alive, but in trouble.”

Severe hospital negligence when his daughter Shira gave birth to twins left her with brain damage, while the Hetzroni family and the wider kibbutz community began taking care of them. Even after his wife and one of his sisters died a few years ago, he kept going, “something between a father and a grandfather, a friend, and a brother.” His sister Ayala, meanwhile, was known in the kibbutz for her work in the children’s home and then later in the printing press. While Avia cared for Shira, Ayala became the “savdoda,” a portmanteau of grandmother and aunt, becoming the legally appointed guardian and recognized “mama” of the twins Liel and Yanai. Now aged 12, she by their side when the murderers came; they all died together in Pessi’s house, an episode I’ll discuss below. Avoyha, meanwhile, was shot elsewhere in the kibbutz; in a particularly nasty irony, it seems that he bled out for hours.

It wasn’t just kibbutzniks who were murdered in Be’eri that day. There was Anula J.W Ratnaya Mudiyanselage from a town near the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo. A 49-year-old mother of two, she had worked as a caregiver in Israel for ten years, and was in Be’eri caring for Ettie Morado, a blind woman in her nineties. “She hid me under the bed and went forward to see what was happening,” Ettie, whose son was also murdered that day, told the media. Anula’s story immediately reminded me of Amichai – a woman “buried in the city that she came from, at a distance of more than a hundred kilometers,” enlarging the “circle of grief considerably.”

And then, at the home of Pessi Cohen, where 14 residents were held (including the Hetzroni twins and savdoda), a name that immediately stuck out: Suhaib Abu Amer Al-Razem, whose story was particularly poignant for us as translators. A 22-year-old Palestinian minibus driver from East Jerusalem, Suhabi had been waiting down the road near the Nova festival to bring partygoers home when the attack began. Footage from October 7 shows him being confronted by Hamas terrorists. Some of them suggested letting him go, but eventually they took him to Be’eri, to Pessi Cohen’s home, where he seems to have been used as a translator. It was here that Brig. Gen. Barak Hiram ordered troops to fire two tank shells at the house (of this decision, the IDF inquiry reads: “The tank fire towards the area near the house was carried out professionally, with a joint decision made by commanders from all the security organizations after careful consideration and a situational assessment was made, with the intent to apply pressure to the terrorists and save the civilians held hostage inside”). It is still not totally clear how everyone inside died; Razem’s body, meanwhile, was only located 12 days later.

“The stories repeat themselves,” Eyal tells us after a while - what I’ve written here is only a fraction of what we heard that day. Du Fu’s whirling chaos and Amichai’s circle of grief extends infinitely. A recent probe has found that the IDF “failed in its mission to protect the residents of Kibbutz Be’eri,” primarily because the military had never prepared for Israeli communities being simultaneously attacked by terrorists. I think back to the discussions in the Whatsapp groups about how to plan trips to the area and to explain October 7 to visiting groups. It’s important to explain the history of Gaza, and the Gaza Envelope, the Disengagement, Hamas, and the ongoing war, but those discussions can take place outside the kibbutz gates. There, in Be’eri, there is only one story, that of an abandoned community that tried to defend itself, but the gates of Gaza weighed too heavily on their shoulders and overcame them.

Incredibly poignant piece.

My heart is broken for these beautiful lives destroyed.