This is the second in a four-part series. For part one, click here.

Although the atomic bomb was ultimately used on Japan, the Manhattan Project was primarily driven by the fear that the Germans might get there first. After late 1944, though, when German defeat became inevitable, the focus switched to Japan. “If it works, and pray God it does,” Roosevelt told his secretary in December 1944, it will save many American lives.” When Truman (who became president when Roosevelt died in April 1945) was told that the bomb would soon be ready, he wrote in his diaries that the “Japs” would surrender “when Manhattan appears over their homeland.”

The controversy over the bombing continues to this day, which is why Overy’s framing of the question in Rain of Ruin is important:

The question asked is usually “was it necessary?”; the question, however, should really be “why was it thought to be necessary at the time?” In short, “the bombs were dropped to force Japanese surrender, end the war quickly, and save American lives. This answer is not wrong, but like the explanation for the firebombing of Japanese cities, the historical reality was far more complex.

The Battle of Okinawa, which ended in June 1945, demonstrated how costly an invasion of Japan’s home islands would be: 12,520 American soldiers were killed, with 82,229 casualties. In August, the Joint Planning Staff estimated that 500,000 would be killed if the home islands were invaded; the Army Service Forces predicted 720,000 dead and wounded if the war lasted until December 1946. Other estimates reached as high as one million; the lowest was 100,000. To put this in context, the defeat of Germany had already resulted in a total of 1,047,115 casualties.

Following the fall of Okinawa, the Japanese began the complete mobilization of the population for the final battle. “THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN” was the response of one intelligence officer. These developments, Overy explains, confirmed “the erosion of any distinction between combatant and noncombatant already evident in the conventional bombing of city centers.” The Japanese Army counted on a 28-million-strong “militia” for the final battle, while a “People’s Handbook of Combat Resistance,” reminiscent of Mohammed Deif’s pre-October 7 instructions, explained how anything could be used as a weapon, “hatchets, sickles, hooks, and cleavers. In karate assault smash the Yankee in the pit of his stomach, or kick him in the testicles.”

At the heart of the problem, explained the Allied Combined Intelligence Committee in June 1945, was that “[the] idea of foreign occupation of the Japanese homeland, foreign custody of the person of the emperor, and the loss of prestige entailed by acceptance of ‘unconditional surrender’ are most revolting to the Japanese.” On July 26, the United States, Britain, and China (the Soviet Union was not yet at war with Japan) signed the Potsdam Declaration, calling for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces, promising “prompt and utter destruction” if this did not happen. Two days later, the Japanese press reported the government’s rejection of the ultimatum, making the dropping of the bomb inevitable: “Japan was an obstacle, and any moral sensitivity about how defeat was to be achieved, already absent in popular enthusiasm for the conventional bombing campaign, had disappeared by the time of Potsdam.”

Like the firebombing campaign, it was disingenuously claimed that the target for the two atomic bombs would be primarily military, with cities defined as industrial and military targets rather than residential areas. “In these calculations,” Overy writes, “human beings were largely absent, though not entirely unacknowledged.” Truman, for example, told Secretary of War Henry Stimson “to use it [the atomic bomb] so that military objectives and soldiers are sailors are the target but not women and children,” a patently impossible task that was “consistent with the way in which Japanese cities had been represented in expediently abstract terms from the onset of the firebombing campaign. The tranquilizing effect of the military language used explains why Truman at the time had no reason to obstruct the bombing and every reason to endorse it.”

On August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul Tibbets dropped the “Little Boy” from the Enola Gay; the bomb exploded 1,800 feet above Hiroshima, destroying all life within a radius of 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, and burning those within five kilometers. This was followed by a blast wave that tore off the skin and damaged the internal organs of those who survived the initial radiation. The thermal radiation up to 500 meters from the hypocenter was 900 times more searing than the sun, while the ionizing radiation left survivors to die slowly from vomiting and diarrhea and bleeding from the bowels, gums, nose, and genitals. This was followed by a firestorm caused by secondary fires, contributing to the destruction of 92 percent of the buildings in the city.

One survivor, Nakamura Setsuko, then a 13-year-old schoolgirl, testified:

They did not look like human beings. Their hair stood straight up; their clothes were tattered or they were naked. All were bleeding, burned, blackened, and swollen. Parts of their bodies were missing, flesh and skin hanging from their bones, some with eyeballs hanging in their hands, and some with their stomachs burst open, their intensities hanging out.

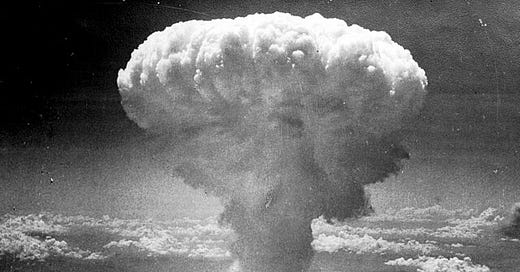

By the end of 1946 118,661 civilians had been killed by the bomb; 112,711 were within two kilometers of the hypocenter. An estimated 20,000 soldiers stationed in a nearby castle also died; this explains the total of approximately 140,000 later presented by Hiroshima to the United Nations. Nagasaki was bombed on August 9; despite the infamous mushroom cloud this was less destructive, although it still killed 73,884 people.

Why were Hiroshima and Nagasaki chosen? Tokyo might have seemed a more obvious choice but was rejected for several reasons. First, the objective of the bomb was to make the Japanese surrender, which wouldn’t be possible if those with the authority to do so were vaporized in a nuclear attack. It was also where the Emperor lived. Second, it was the center of Japanese government; destroying it with a nuclear bomb would have made administering the country after the war extremely difficult. Finally, it had already been terribly damaged during Operation Meetinghouse, making it less susceptible to nuclear attack. Kyoto, Japan’s former capital, was also touted as a target. It was an important historical and cultural center with a large population and was preferred by the U.S. military and President Truman. Secretary of War Stimson, though, demanded that it be removed from the list, because he thought the Japanese would never forgive America for destroying such a key center of their cultural heritage. Some also ascribe his way of thinking to the fact that he had visited the city himself, although Overy downplays this. Hiroshima was chosen because it housed a major military base, while Nagasaki was actually a backup target; because of its weapons factories, Kokura was first choice, but the smoke from its factories combined with cloud cover meant the target couldn’t be seen properly, so Nagasaki was attacked instead.

Truman was initially proud of the outcome, saying: “What has been done is the greatest achievement of organized science in history. It was done under high pressure and without failure.” In 1948, though, he told David Lilienthal, head of the Atomic Energy Commission: “You have to understand that this isn’t a military weapon. It is used to wipe out women and children and unarmed people, and not for military uses.” The dropping of the atomic bombs marked a crossing of the Rubicon from which humanity has never returned; since then, we have all lived under the spectre of total annihilation. Why, then, was it thought to be necessary, and why were the Japanese so reluctant to surrender? I’ll examine this question in part three tomorrow.

Excellent write-up!

As I understand, there were overtures for conditional Japanese surrender prior to August 1945, but they were not deemed politically feasible. With 110,000 dead service members in the Pacific war, any US president who demanded less than total victory over Japan would be politically ruined. I’m curious of your views on the domestic politics of the decision making process.

You touch on this in the articles—one wonders how much hand-wringing that generation of US military war planners actually did over the firebombing and nuclear bombs on Japan.

It was only 5-6 years later when air strikes and bombing of North Korea were even more devastating than that of Japan: some 15% of their population, according to later remarks by LeMay, which works out to be 1-2 million people, died as a result and there was no pretext of an mass-casualty mainland invasion under consideration and most of the bombing happened after the war has settled into statement at the end of 1950. We bombed them into the Stone Age simply because we could, eventually running out of targets. If the morality of inflicting mass-death on the Japanese was something American leadership agonized over, they seemed to have gotten over those qualms in Korea.