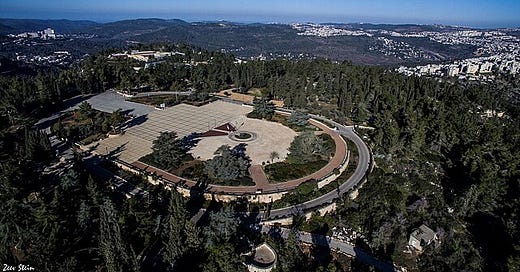

Guest Post: On the Slopes of Mount Herzl

On what it's like to have spent the past year living opposite Israel's biggest military cemetery

For the first time I hand over the Love-of-the-Land reins, to my wife Merav, with a piece (translated from Hebrew by myself) about living opposite Mount Herzl and giving birth during a year of war.

“What’s it like to live next to Mount Herzl?” we asked someone in our building, when we saw our apartment for the first time. “The neighbors are very quiet,” one told us. Once a year, on Yom Hazikaron, our street fills up with soldiers and the exits are blocked, but when Yom Haatzmaut begins at night there’s a wonderful view of the fireworks from our balcony. Another friend was horrified – “It’s really beautiful here, but how can you raise children opposite a military cemetery?!” I laughed and said: “In their death they commanded us to live.”

It’s true, once a year, around Pesach time, we start to hear the frantic rehearsals for the ceremony. I already know the playlist of songs at least a week beforehand; several times, when rehearsals continued deep into the night at a volume that threatened to wake up the kids, in a burst of righteousness, I even considered calling the police to complain. The rest of the time we have the privilege of looking at the green mountain safe in the knowledge that nobody will cover it with a housing project or ugly towers. Over the years, I’ve filled the balcony looking out over the mountain with flowering plants. Every time one of them dies, I go to the nursery and buy five more. Slowly, my blossoming balcony has provided the perfect framing for the view of the mountain.

A few days after Simchat Torah, when the number of hostages, injured, and dead was still being updated daily in red graphs on the news sites, the funerals began on Mount Herzl. They began early in the morning and finished well after midnight. One after the other without pause for weeks. I heard fragments of words, half sentences, heartbreaking tears. El Malei Rachamim. A three-volley salute. Worst of all, the calls for mourners to quickly depart so the next funeral can begin. Somehow that’s what I heard clearer than anything – every single word. That’s how it was for weeks. I didn’t know it then, but those same weeks, new life was growing inside me.

With time, there were fewer funerals. The terrible announcer calling for the mourners to leave the mountain fell silent. There were even weeks without any funerals at all. Only the sound of warplanes in the skies above didn’t relent. Once every few days there was another funeral, or even two or three in the same day. Sometimes it was someone well known – like Arnon Zamora, who was killed rescuing Noa Argamani, Almog Meir Jan, Andrey Kozlov, and Shlomi Ziv from Hamas in Nuseirat; or Ori Danino, who was murdered in a dark tunnel underneath Rafah, together with Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Eden Yerushalmi, Carmel Gat, Alex Lobanov, and Almog Sarusi. On those days, the street filled with vehicles, and traffic jams blocked the neighboring streets. On other occasions it was less well-known soldiers, and I only knew there was a funeral when mourners asked me for directions.

In this way, the dead accumulated and my pregnancy advanced, weighing me down more and more. The heaviness of the pregnancy shook up my world, while also holding me in place. I listened to the funerals like it was my contribution to the war effort, my sad participation.

In the beginning, my daughters didn’t ask anything. They even ignored the three-volley salute. Perhaps they were so prepared for sirens that they classified any other strange sound as unimportant. Or maybe they understood that it wasn’t worth them knowing what those sounds and voices signified. After a few months, though, they began to ask – "Ima, what are those voices? “It’s someone praying,” I answered. “He’s praying for the people injured in the war.” Over time, I realized it was impossible to continue with these evasive answers. Last night Achinoam, my youngest daughter, asked me again: “What’s that ima?” I told her they were burying a soldier who had been killed in the war. She looked at me in silence.

Nine months and two days after October 7, on a Tuesday afternoon, I gave birth to a baby boy. He immediately opened his big eyes, surprised and curious. “Wow – look at how he opens his eyes! He looks like a one-month-old baby,” the nurses at the maternity ward said in wonder. Yes, I thought to myself, he probably knows that in this world there’s no time to waste. We thought about naming him after someone who had been killed on October 7 but decided it would be too heavy a burden to bear. Instead, we called him Hillel Haim, a combination of ancient wisdom and life. Now, since the start of ground operations in Lebanon, the funerals have picked up again, although thankfully there are far fewer than a year ago. Sometimes Hillel’s crying mingles with the wailing of the mourners on the mountain, and it breaks my heart. In death they commanded us to live and all that, but it rings hollow amidst all this sorrow.

Tear to my eye

Beautiful. L’Chayim.